There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Many students chase speed as the final goal of exam preparation. They write faster.

They finish papers early.

They pride themselves on “getting everything down.” And yet, under real exam pressure, something strange happens. Speed disappears.

Structure collapses.

Thinking fragments. Psychology explains why. Speed is not a cognitive skill on its own. It is a by-product of structure. When students practise writing quickly without a clear internal structure, they rely heavily on working memory. Working memory is fragile. It can handle only a limited number of ideas at once. Under calm conditions, this may feel manageable. Under exam stress, it fails. Stress increases cortisol, which directly impairs working memory and reduces activity in the prefrontal cortex—the brain region responsible for planning, organisation, and inhibition. When structure is not automated, the brain must rebuild it on the spot. Under pressure, it simply can’t. This is why speed-only preparation collapses. Students who write quickly without structure often experience:

References:

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer.

Speed in exams is not a skill—it is the outcome of structured thinking automated through practice.

Under pressure, the brain relies on what’s automated.

In exams, speed is not trained — it is revealed.

When thinking is structured, the brain stops panicking and starts executing.

The core ideas come from John Sweller, who introduced Cognitive Load Theory in the late 1980s. Sweller showed that learning and performance are constrained by the limited capacity of working memory, especially under pressure. His work demonstrated that how information is structured matters more than how fast it is processed. Later refinements with Paul Ayres and Slava Kalyuga expanded this into a full theory of learning, expertise, and automaticity.

Advice for IB students

Stop chasing speed. Build structure first.

IB exams reward organised thinking under pressure, not rushed writing. Learn how to unpack command terms, plan answers, and position studies and evaluation before you practise writing fast. When structure is clear and repeatedly practised, it becomes automatic—freeing your working memory to explain, analyse, and evaluate even under stress. Speed will emerge on its own as a result of confidence and reduced cognitive load. In IB exams, the students who score highest are not the fastest writers, but the ones whose thinking stays stable, coherent, and controlled when pressure rises. Every learner’s IB Psychology journey is different.

Share a few details so we can guide you with clarity, care, and academic precision. Stay informed with insights on how IB Psychology builds thinking skills, confidence, and long-term understanding of simple exam strategies, clarity notes, and reflections that help you think better.

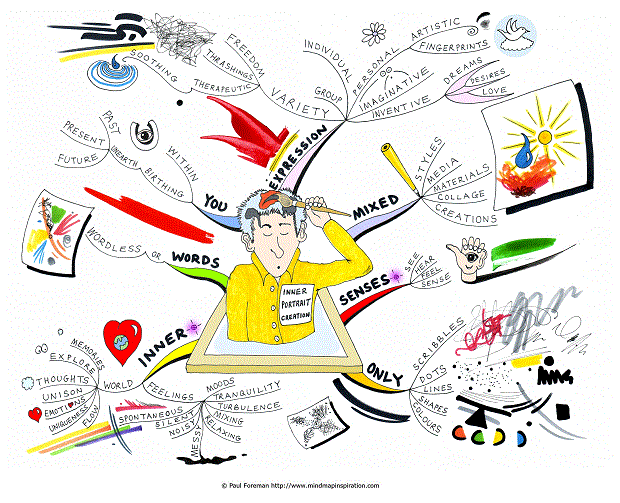

Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988) Cognitive Load Theory explains that working memory can handle only a small amount of information at once. When students write fast without structure, they overload working memory—especially under stress, when cortisol further reduces prefrontal cortex efficiency. This directly explains why speed collapses in exams: the brain is forced to juggle ideas, decisions, and organisation simultaneously, leading to fragmentation, repetition, and blanking out. Structure reduces extraneous cognitive load, protecting thinking under pressure. Schema Automation (within Cognitive Load Theory) A crucial extension of Sweller’s work is schema automation. When students practise structured answers repeatedly, the structure becomes a schema stored in long-term memory. During exams, this schema activates automatically, shifting control away from fragile working memory. As a result, fewer decisions need to be made in real time, freeing cognitive resources for explanation, analysis, and evaluation. Speed then emerges naturally as a by-product of automation—not effort.