There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

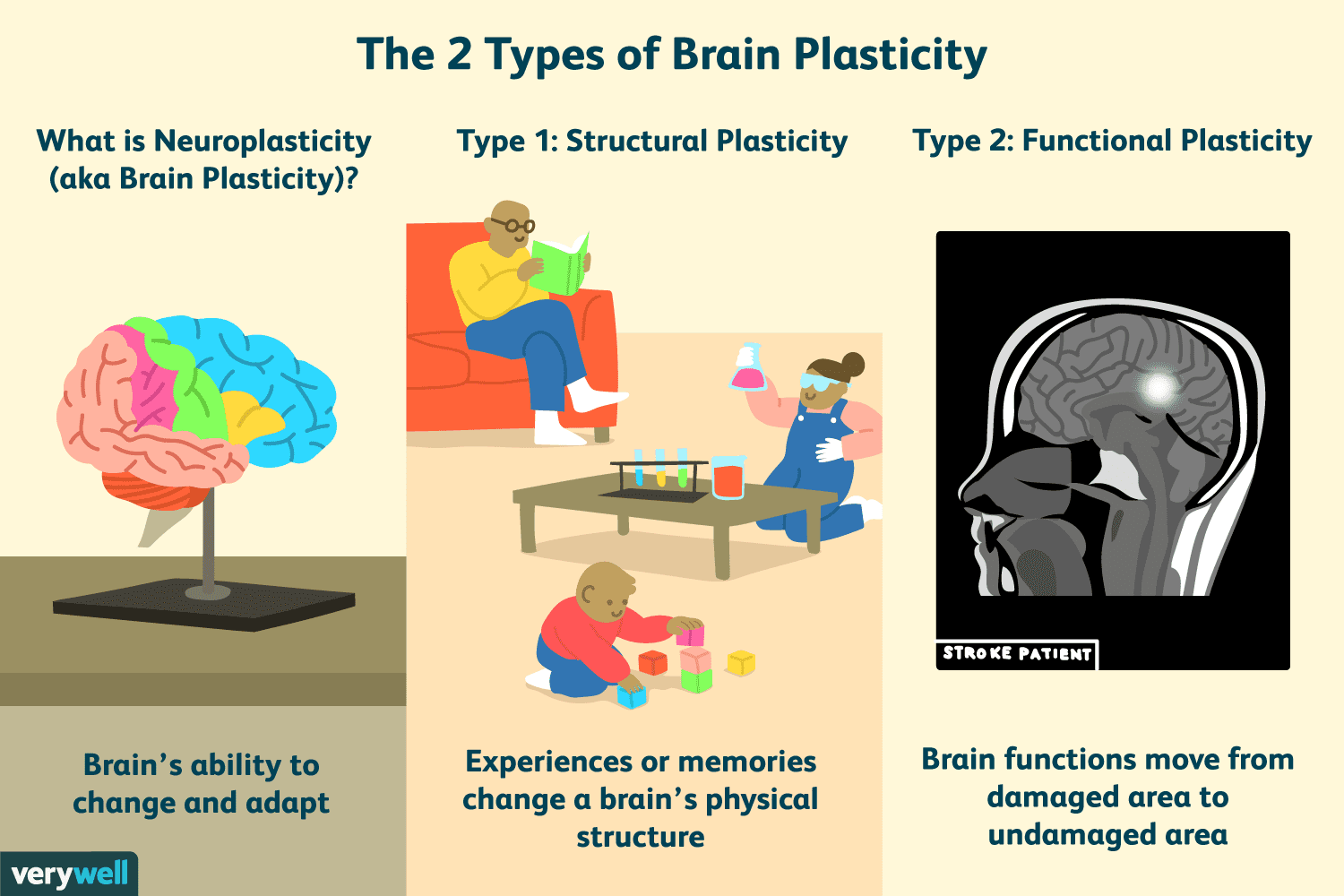

At the heart of effective learning lies a simple but powerful truth: the brain is not fixed. Modern neuroscience shows that the brain continuously reshapes itself in response to experience, effort, and challenge—a property known as neuroplasticity. Long before this science entered popular discourse, the philosophy of the International Baccalaureate Learner Profile quietly reflected this understanding. Attributes such as Risk-taker, Reflective, Inquirer, and Open-minded are not just educational ideals; they are deeply aligned with how the brain actually grows.

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganise neural connections based on repeated use, effort, and feedback. When learners engage deeply with material—especially when it feels difficult—neurons involved in that process fire together, strengthen their connections, and become more efficient over time. This means learning is not about absorbing information passively, but about actively stretching cognitive capacity.

Importantly, the brain does not grow most when tasks are easy. It changes most when learners operate at the edge of their competence—when they are challenged, make errors, reflect, and try again. From a neurological perspective, struggle is not a sign of failure; it is a signal that learning is taking place.

A growth mindset is the belief that ability can be developed through effort, strategy, and reflection. This belief is not motivational rhetoric—it mirrors the biological reality of neuroplasticity. When students believe that intelligence is malleable, they are more willing to engage with difficult tasks, persist through confusion, and revise their thinking after mistakes.

Conversely, a fixed mindset discourages neural growth. If students interpret difficulty as evidence of incapacity, they avoid challenge, reducing opportunities for the brain to adapt. Over time, this avoidance limits learning—not because of lack of ability, but because of lack of engagement with productive difficulty.

Within the IB Learner Profile, Risk-taker is often misunderstood. It does not mean being careless or impulsive. Neurologically, risk-taking in learning means tolerating uncertainty, attempting unfamiliar problems, and articulating ideas that may not yet be fully formed.

These moments of uncertainty are crucial for neuroplastic change. When learners step outside rehearsed answers or memorised templates, the brain must integrate information across networks—frontal regions for reasoning, hippocampal systems for memory, and emotional regulation systems for confidence. This integration strengthens learning far more than repeating what is already known.

The IB’s emphasis on inquiry, higher-order thinking, and reflection aligns closely with how learning consolidates in the brain. Challenge forces the brain to:

inhibit automatic responses,

evaluate alternatives,

and restructure understanding.

Each of these processes increases cognitive resilience. Students who regularly engage with challenge develop not only stronger academic skills, but greater tolerance for complexity—an ability essential both for examinations and for life beyond school.

Reflection is the bridge between experience and long-term learning. When students reflect—on errors, strategies, or changes in understanding—they reactivate neural pathways, strengthening them further. This is why reflection is a core IB attribute: it biologically reinforces learning by stabilising new neural connections.

Without reflection, effort may remain temporary. With reflection, learning becomes durable.

What makes the IB Learner Profile powerful is that it does not ask students to “be better learners” through willpower alone. Instead, it cultivates dispositions that naturally support neuroplastic growth:

Inquirers seek novelty, stimulating new neural pathway

Risk-takers embrace uncertainty, promoting integration across brain systems

Reflective learners consolidate learning biologically

Open-minded learners adapt cognitive frameworks rather than rigidly defending them

In this sense, the Learner Profile is not just educational philosophy—it is learning biology in action.

When students understand that challenge reshapes the brain, struggle becomes meaningful rather than threatening. Growth mindset stops being motivational language and becomes a scientific reality. Risk-taking becomes a neurological necessity, not a personality trait.

The IB approach works because it aligns learning with how the brain actually develops. Education, at its best, does not fight biology—it works with it.

References: Draganski, B. et al. (2004). Neuroplasticity: Changes in grey matter induced by training.

Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I. Q. (1998). Brain plasticity and behavior.

Growth mindset and grit are closely connected because both are rooted in the brain’s capacity to adapt through sustained effort. A growth mindset reflects the understanding that abilities develop with practice, while grit is the willingness to stay engaged with difficulty over time. Neuroscientifically, repeated effort in the face of challenge strengthens neural pathways, making persistence biologically meaningful rather than purely motivational. When students believe improvement is possible, they are more likely to persevere through setbacks; when they persevere, the brain reorganises to support higher levels of performance. Together, growth mindset provides the belief that growth can happen, and grit provides the behaviour that allows it to happen.

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to change its wiring based on what you repeatedly do, think, practise, and experience. Every time you revise a concept, explain it aloud, apply it to a new question, or even struggle with a difficult problem, your brain is not just “remembering” — it is physically reshaping neural pathways.

Before the IB exam:

Neuroplasticity allows your brain to strengthen the pathways you use most during revision. When you practise understanding concepts, applying them to questions, and explaining ideas in your own words, the brain builds faster and stronger connections between memory and thinking areas. This is why consistent, concept-based revision makes recall quicker and more reliable than last-minute memorisation.

During revision practice:

Each time you retrieve information—through timed practice, writing answers, or correcting mistakes—the brain reinforces those neural routes. Even errors help, because correcting them refines understanding and updates memory. Over time, this makes thinking more automatic and reduces the chances of blanking out under pressure.

During the IB exam:

Neuroplasticity helps the brain stay flexible when questions look unfamiliar. Well-trained neural networks allow you to adapt known concepts to new contexts, interpret command terms accurately, and structure answers logically. This is why students who understand ideas deeply can handle unseen questions more calmly.

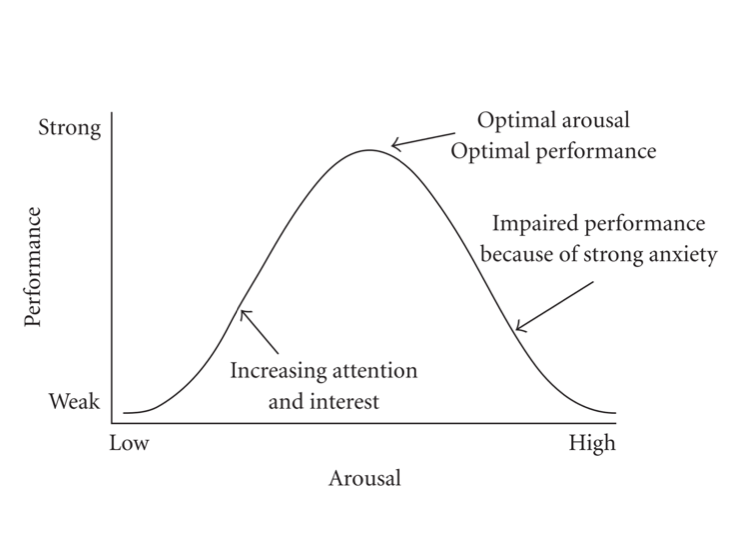

Under exam stress:

A brain trained through regular practice is better at managing stress. Neuroplastic changes support the prefrontal cortex—the thinking part of the brain—so anxiety is less likely to take over. This helps you stay focused, recover quickly from difficult questions, and perform closer to your true ability.

Every learner’s IB Psychology journey is different.

Share a few details so we can guide you with clarity, care, and academic precision. Stay informed with insights on how IB Psychology builds thinking skills, confidence, and long-term understanding of simple exam strategies, clarity notes, and reflections that help you think better