There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Confidence is often mistaken for personality.

Some people “have it.” Others don’t. Neuroscience tells a very different story. Confidence is not a trait—it is a neurological outcome of repeated successful regulation. When students feel confident walking into an exam, it’s not because they told themselves positive affirmations. It’s because their brains have learned, through experience, “I know how to handle this situation.” That learning happens at the neural level. Every time a student practises answering questions under exam-like conditions—timed writing, planning under pressure, choosing studies—the brain engages the prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for executive control, decision-making, and self-regulation. When those attempts are even moderately successful, the brain releases dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with reward and goal-directed behaviour. Dopamine doesn’t just feel good.

It reinforces neural pathways. The brain marks those patterns as useful and efficient: “This strategy worked. Use it again.” Over time, these reinforced circuits become easier to activate. What students experience subjectively as confidence is, biologically, reduced effort and faster access to effective strategies. At the same time, something important happens to stress regulation. Early exam practice often triggers high cortisol levels. Cortisol prepares the body for threat, but in excess it disrupts memory retrieval and flexible thinking. However, when students repeatedly face similar challenges and survive them successfully, the brain recalibrates its threat response. Cortisol spikes become smaller and shorter. This is not emotional toughness—it is neural adaptation. The amygdala, which detects threat, becomes less reactive. The prefrontal cortex gains greater top-down control. The result is a calmer physiological state during exams, allowing clearer thinking and better organisation. Confidence, then, is the brain learning that the situation is manageable, not dangerous. There is also a memory component. Repeated successful experiences strengthen connections in the hippocampus, linking context (“exam questions,” “time pressure”) with effective responses (“plan first,” “select studies carefully”). This creates a sense of familiarity. And familiarity reduces anxiety. This explains a powerful observation in education:

students often feel more confident after doing practice papers—not before. Not because they learned more content, but because their brains learned what to do. Importantly, confidence grows fastest when challenges are slightly above comfort level, not overwhelming. Tasks that are too easy don’t trigger growth. Tasks that are too hard trigger shutdown. The brain builds confidence when effort is required and success is achievable. This balance is critical. This is why structured guidance matters. Unguided struggle can increase stress. Guided challenge builds confidence. When students understand why an approach works, not just that it works, neural learning deepens and transfers across situations. So confidence is not something to summon on exam day. It is something the brain earns through training. And once built, it doesn’t disappear easily—because it lives not in motivation, but in neural circuitry shaped by experience.

References:Schultz, W. (1998). Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons.

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function.

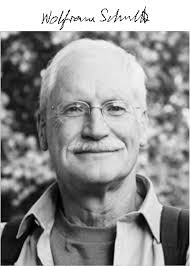

1. Dopamine and Reward-Based Learning Discovered and formalised by Wolfram Schultz

Schultz demonstrated that dopamine neurons fire in response to successful outcomes and predictions of success, not just pleasure. This led to the theory of reward prediction error, which explains how the brain learns which strategies are effective. In the context of exams, when a student successfully plans or answers a question under pressure, dopamine reinforces the neural pathways involved. Over time, these pathways become easier to activate, making effective strategies feel natural and automatic. What students experience as confidence is, biologically, the brain recognising a familiar, rewarded pattern.

Achor shows how positive expectancy and repeated success prime the brain for better performance, supporting your point that confidence emerges after the brain learns “I can handle this.”

Dweck explains how confidence grows from learning processes and successful regulation, not from fixed traits. This aligns directly with your argument that confidence is built through experience, feedback, and neural reinforcement, not affirmations.