There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Students are often told the same thing before exams: “Just stay calm.”

It sounds helpful. It sounds wise.

But psychology draws an important distinction that is often missed. Calm is a state. Control is a skill. Calm refers to low emotional arousal. Control refers to the brain’s ability to regulate attention, behaviour, and decision-making, even when arousal is present. Exams rarely reward calmness alone—they reward regulated engagement under pressure. From a neurological perspective, control is governed largely by the prefrontal cortex, which manages planning, inhibition, and flexible thinking. Calmness without control can actually reduce performance if arousal drops too low. Students may feel relaxed but unfocused, disengaged, or mentally sluggish. This explains a common paradox: students who feel very calm sometimes underperform. In contrast, students who feel slightly tense but mentally organised often do better. Their brains are alert, motivated, and actively managing the task. This is controlled arousal, not calmness. Calmness becomes a problem when it is achieved through avoidance—avoiding timed practice, avoiding challenging questions, avoiding evaluation. The brain stays comfortable but untrained. On exam day, when pressure appears, control collapses because it was never built. Control is learned, not wished into existence. It is developed through repeated exposure to challenge with structure—planning answers, practising under time constraints, learning how to recover when thinking slips. These experiences strengthen top-down regulation, allowing the brain to stay functional even when stress is present. Calm may feel good.

Control is what performs.

This insight is grounded in research on prefrontal cortex regulation and executive functioning, particularly the work of Arnsten (2009) and Diamond (2013), building on the Yerkes–Dodson principle of optimal arousal.

References:Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions.

Amy Arnsten

She demonstrated how moderate stress optimises prefrontal cortex control, while too little or too much arousal impairs executive functions like attention, inhibition, and decision-making.

Adele Diamond

She formalised executive functions (inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility) and showed that self-regulation, not calmness, predicts performance in demanding tasks.

Foundational background:

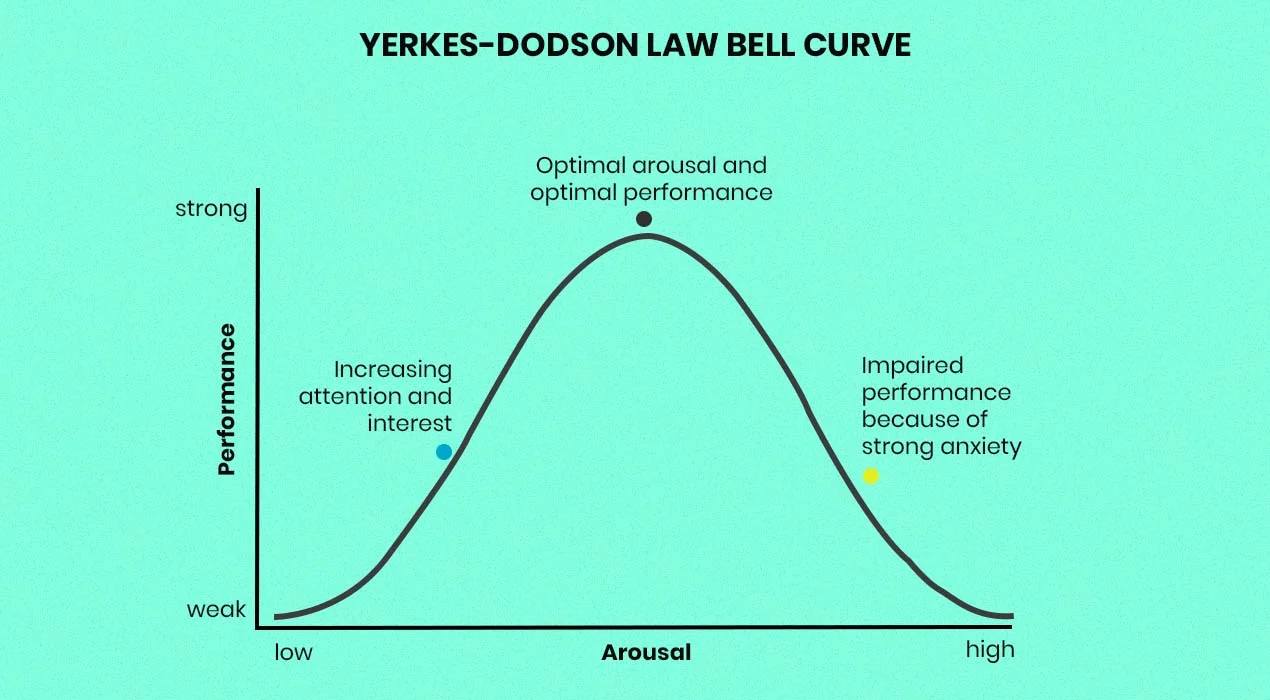

The performance curve implied here traces back to the Yerkes–Dodson law (1908), which showed that optimal performance occurs at moderate arousal, not at complete calm.

Peak performance emerges when the brain is alert, engaged, and in control—not when emotions are completely muted. Moderate arousal activates attention systems, sharpens working memory, and energizes goal-directed behavior through the prefrontal cortex. When arousal drops too low, thinking becomes passive and unfocused; when it rises too high, control collapses into anxiety and impulsivity. The skill that matters, especially in exams or high-pressure tasks, is the ability to regulate arousal—maintaining focus, planning, and flexibility even while feeling some tension. In other words, success is not about feeling calm, but about staying cognitively organized under pressure.

The Yerkes–Dodson law, proposed by Robert Yerkes and John Dodson, explains that performance improves with increasing arousal—but only up to an optimal point. Beyond this point, further stress causes performance to decline. This law directly anchors the message of this blog for IB students: exams do not reward being completely calm, nor do they reward panic. They reward regulated arousal—a state where the brain is alert, motivated, and under control.

This talk focuses on physiological and cognitive regulation under pressure rather than calmness. Cuddy shows how posture, embodiment, and intentional behaviour can shift arousal into a controlled, performance-ready state. It reinforces the idea that you don’t need to eliminate stress—you need to manage how your body and brain respond to it, keeping confidence, focus, and decision-making intact in high-stakes situations like exams or presentations.

IB exams demand sustained attention, structured thinking, and flexible application of concepts under time pressure. According to Yerkes–Dodson, the goal is not to eliminate stress before exams, but to train the brain to operate in this optimal middle zone through timed practice, retrieval, planning frameworks, and exposure to challenge. Students who follow this principle stop chasing calmness and instead build control—exactly what IB assessments are designed to test.